Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare and the Basic Survey on Wage Structure

●Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (厚生労働省)

The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) is one of Japan’s central government ministries, responsible for safeguarding the nation’s overall health and welfare as well as managing labor policies. Its scope covers a wide range of fields, including healthcare, social security, pensions, and employment. In terms of labor policy, the MHLW plays a key role in addressing issues such as wages, job security, and working conditions.

The ministry also publishes official statistics and survey results on a regular basis, providing reliable data that serves as a foundation not only for policymakers, but also for researchers, businesses, and the general public. Because of its broad mandate and credibility, the MHLW is considered one of the most authoritative sources of labor-related information in Japan.

●Basic Survey on Wage Structure (賃金構造基本統計調査)

Among the many surveys conducted by the MHLW, the Basic Survey on Wage Structure is one of the most important sources of wage statistics in Japan.

Conducted annually, this nationwide survey examines wage levels in detail by factors such as occupation, age, gender, educational background, company size, and region. It distinguishes between “general workers” and “short-time workers,” which makes it possible to capture differences between regular and non-regular employees as well as wage disparities across gender and age groups.

Because of its comprehensive scope and consistency, this survey is widely used to analyze long-term wage trends and to study issues of inequality in the Japanese labor market.

General Workers as Defined by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare

● General Workers in MHLW Statistics

In the statistics published by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW), general workers refer to all wage earners employed for a period exceeding one month, across all industries and occupations. This category includes not only regular employees but also contract workers and dispatched workers.

● Occupations Included

・Company employees (clerical, technical, managerial)

・Service industry workers

・Manufacturing workers

・Professionals (doctors, teachers, researchers, etc.)

・Dispatched workers, contract employees

※In other words, all wage earners employed for more than one month, regardless of industry or occupation, are classified as general workers.

● Cases Excluded

・Workers employed for one month or less

・Part-time and hourly workers → Counted separately as short-time workers (短時間労働者, Tanjikan Roudousha)

・Self-employed persons, freelancers, and those engaged in agriculture, forestry, or fisheries as self-employment → Not included in the survey

Trends in Wages by Gender in Japan

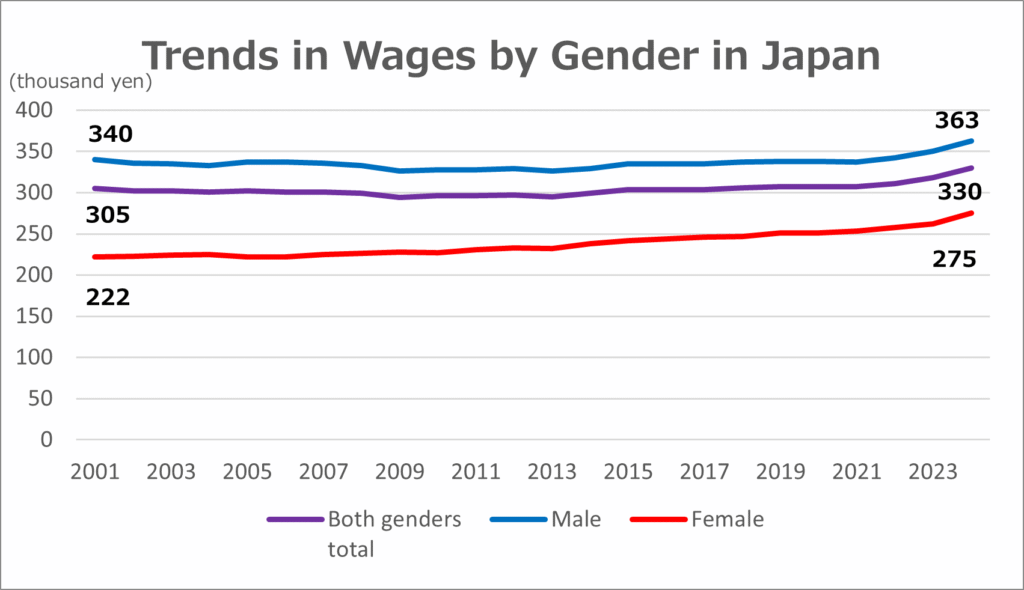

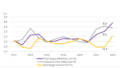

Comparing the data from 2001 and 2024, the wages of general workers in Japan show an overall upward trend. The average wage for both genders rose from about 305,000 yen in 2001 to around 330,000 yen in 2024. During the same period, the average wage for men increased from roughly 340,000 yen to 363,000 yen, while women’s wages rose significantly from about 222,000 yen to 275,000 yen. Women’s wages grew by approximately 24%, which is much higher than the 7% growth rate for men.

Nevertheless, the gender wage gap remains significant. In 2001, women earned about 65% of men’s wages, and even in 2024 the figure is only 75%. More than 20 years have passed, yet the gap has not been closed, and the pace of improvement has been slow.

This situation is closely tied to the structure of Japanese society. Traditionally, men have been expected to participate in the workforce while women were responsible for household duties and childcare. Although dual-income households have been increasing and women’s labor force participation has risen in recent years, career interruptions due to childbirth and childcare still have a major impact on women’s wages. Furthermore, many women are employed in non-regular or part-time positions with lower pay, which reinforces the wage disparity.

That said, the Japanese government has been implementing various policies to expand women’s participation in the workforce. Improvements to childcare leave systems, expansion of childcare services, and initiatives to increase the number of women in managerial positions are gradually making a difference. Women’s employment rates have been rising steadily, and the so-called “M-shaped employment curve,” where women’s employment rates dropped sharply in their 30s, is slowly flattening out.

Even so, Japan’s gender wage gap remains larger than the OECD average, and the low representation of women in mid-level and managerial positions continues to be a serious challenge. Thus, while women’s wages are steadily increasing, it is clear that male-centered work practices and career interruption issues must be fully addressed before the wage gap can be significantly reduced.

[Trends in Wages by Gender in Japan PDF]

Wages by Gender and Age Group in Japan

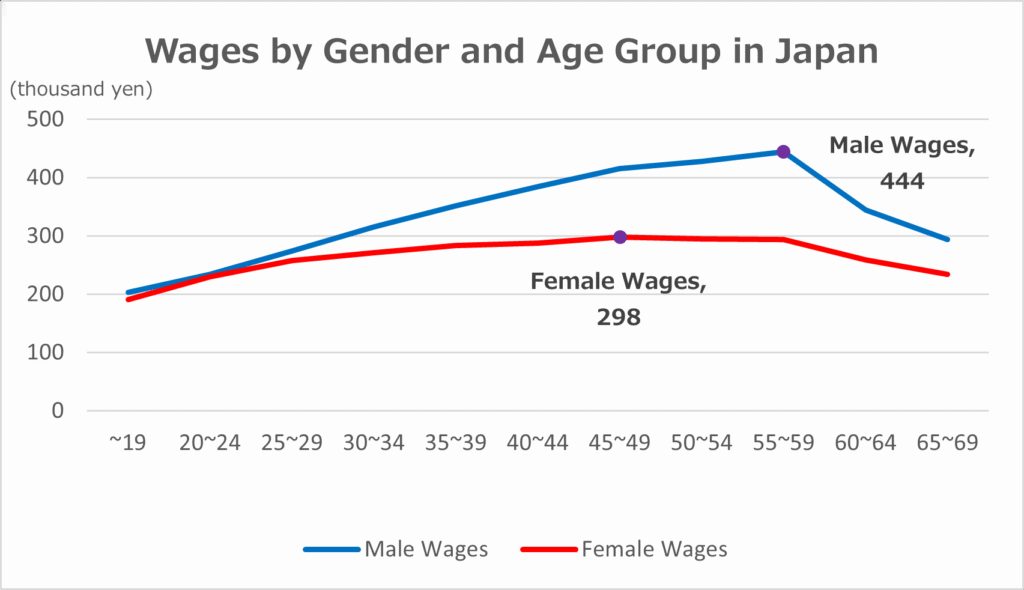

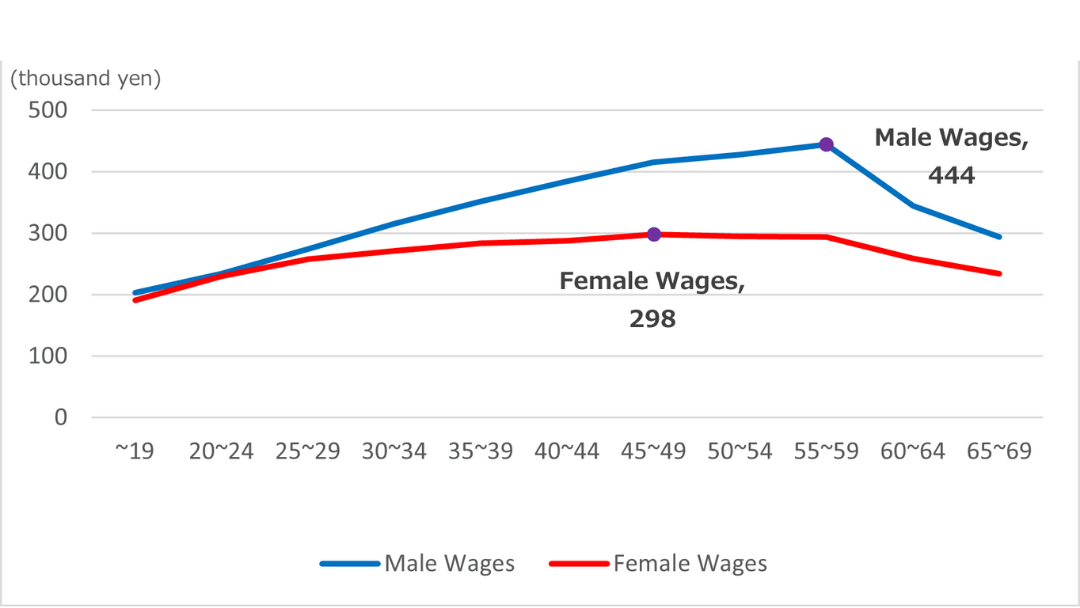

Looking at the data by age group, the characteristics of Japan’s wage structure become clear.

For men, the average wage peaks in the 55–59 age group, reaching about 444,000 yen. This reflects Japan’s traditional seniority-based wage system, in which salaries increase steadily with age and job rank. However, after the typical retirement age of 60, wages drop sharply — to about 344,000 yen for ages 60–64 and 294,000 yen for ages 65–69. This decline reflects reemployment or conversion to non-regular contracts after retirement, where salaries are generally lower.

For women, the wage curve is relatively flatter. From the early 20s to the late 30s, wages rise steadily, but after the 40s they level off and show little further growth. Women’s maximum average wage is around 290,000–300,000 yen in their 50s, which is only about two-thirds of the male peak. Like men, women also experience a sharp wage decline after the retirement age of 60.

This disparity is closely related to social structures in Japan. Early in their careers, women earn wages similar to men, but after marriage, childbirth, and childcare, they often face career interruptions or shift into non-regular employment. As a result, the wage gap widens from the 30s onward, and with fewer women in managerial and senior positions, opportunities for further wage growth are limited. Men, on the other hand, tend to follow a typical seniority-based wage curve, with income rising until their 50s as they gain seniority within the organization.

In summary, both men and women reach peak earnings in their 50s, after which wages drop sharply due to retirement. However, women’s wages remain significantly lower than men’s, and their growth potential is much more limited, highlighting the persistent gender wage gap in Japan.

These statistics reveal that a deep-rooted gender wage gap still exists within Japan’s wage structure. At the same time, wage levels are gradually changing, with policy improvements and shifts in social awareness working together to bring about greater balance. For anyone seeking to understand working life in Japan, this data provides essential background knowledge.

[Wages by Gender and Age Group in Japan PDF]

The Reality of Japanese Companies as Experienced by a Foreigner

I am a Korean who has lived in Osaka and worked for about ten years, during which I experienced four different companies. Please note that my personal experiences cannot represent all Japanese companies, as they are purely individual and subjective. In addition, I have also referred to stories from people around me.

1. About 70% of part-time and temporary workers are women

I mainly worked in office positions, and from my experience, about 70% of non-regular employees such as part-time or temporary workers were women. This may be because of the office environment, but even in warehouses and on-site jobs, there were also many female workers.

2. Most managerial positions are held by men

Japan has traditionally been a male-dominated society, and although attitudes have changed in recent years, most of the managerial positions in the companies I worked for were occupied by men. Of course, this does not mean that promotion is decided solely by gender, but in many cases men were promoted earlier, with factors such as age and family responsibilities taken into account.

3. Executives are almost all men

Unfortunately, I never encountered a female executive in the companies I worked for. While women with ability and experience can naturally rise to managerial positions, very few seem to reach executive-level roles.

4. The seniority-based system

The seniority-based system refers to Japan’s traditional wage structure in which salaries increase according to age and years of service. As mentioned in the managerial positions, salary often rises more due to age and tenure rather than actual skills or performance. While long service in one company can certainly bring valuable experience, I sometimes wonder if it truly reflects a fair evaluation of an individual’s ability and achievements.

Comments