Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC) and Consumer Price Index (CPI)

●Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (総務省)

The Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC) is one of Japan’s central government ministries, responsible for managing the fundamental structure of public administration and overseeing national statistics. It publishes key statistics on demographics, the economy, labor, and prices, providing reliable data essential for policymaking, academic research, and corporate activities. For this reason, MIC is often described as Japan’s “data hub.”

Within MIC, the Statistics Bureau of Japan plays a core role in conducting surveys and compiling statistics. The Bureau releases crucial indicators such as the Consumer Price Index (CPI), household surveys, and labor-related data, all of which are indispensable for understanding Japan’s economy. Wage statistics published by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare also incorporate CPI figures from MIC, showing the close connection between the two institutions.

●Consumer Price Index (CPI)

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) is a statistical measure that reflects changes in the prices of goods and services typically purchased by households. In simple terms, it shows how much the cost of living has risen. The index covers essential categories such as food, clothing, housing, transportation, and medical expenses, making it the most widely used indicator for measuring inflation.

In Japan, the Statistics Bureau under MIC compiles and publishes the CPI every month, using a base year index (currently 2020=100). This index is widely applied in monetary policy, fiscal policy, and business decision-making, such as wage and price setting. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare also relies on the CPI to adjust nominal wages and calculate real wages, highlighting CPI’s crucial role in linking wage and price statistics.

※e-Stat is the official statistics portal site of the Japanese government, providing access to a wide range of statistical data released by various ministries and agencies in one place. By clicking the URL below, you can directly view the Consumer Price Index (CPI) data published by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications.

Nominal Wages and Real Wages

●Nominal Wages

Nominal wages represent the actual amount of money workers receive in their paychecks. This figure usually includes base salary, bonuses, and allowances before tax, and it does not take price changes into account. As a result, even if nominal wages appear to rise, this does not necessarily guarantee an improvement in living standards if living costs are rising at the same time.

For example, if wages increase by 3% compared to the previous year but prices rise by 4%, nominal wages have gone up, yet purchasing power has effectively decreased. Thus, nominal wages are useful for understanding wage levels themselves but have limitations when it comes to evaluating the real standard of living.

●Real Wages

Real wages are calculated by adjusting nominal wages with the Consumer Price Index (CPI), showing how much purchasing power those wages actually represent. In simple terms, real wages indicate how much goods and services workers can buy with their income, making this measure crucial for understanding living standards and the real impact of economic growth on households.

An increase in real wages means that even after accounting for inflation, workers’ standard of living has improved. Conversely, a decline in real wages indicates that price growth has outpaced wage growth, making everyday life more difficult despite nominal wage increases. This is why policymakers and businesses closely monitor changes in real wages in addition to nominal wages.

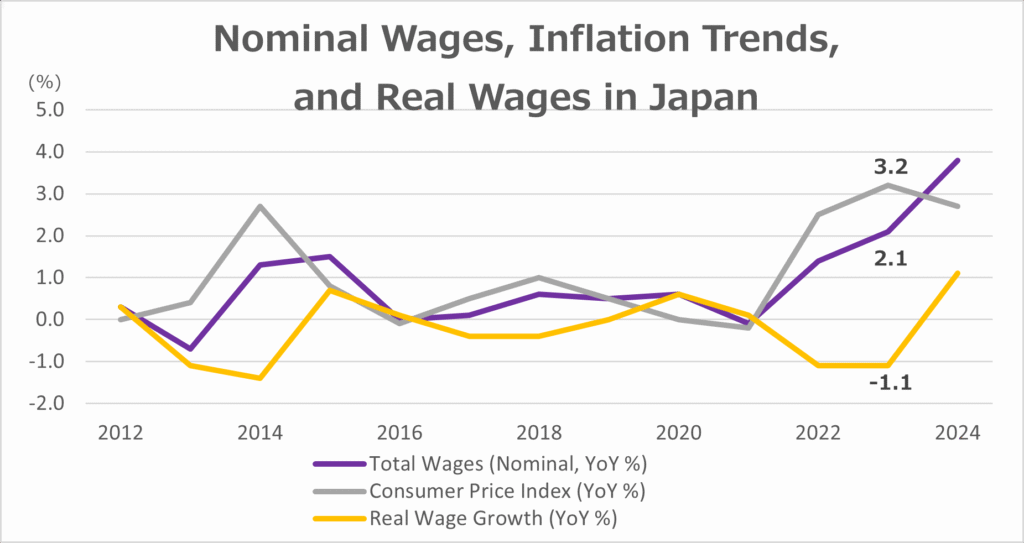

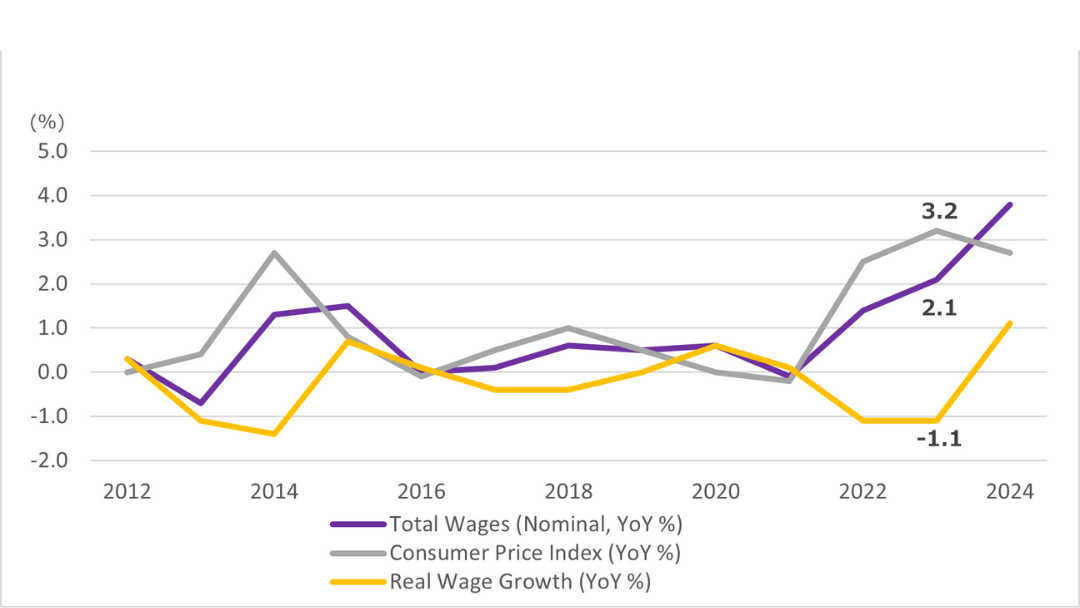

Nominal Wages, Inflation Trends,

and Real Wages in Japan

For this graph, I calculated the growth rate of real wages by simply subtracting the year-on-year change in consumer prices published by the Statistics Bureau (MIC) from the year-on-year change in nominal wages published by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW). In other words, I used a straightforward formula: “wage growth – price growth.” This method is easy to understand and sufficient to illustrate overall trends, but it should be noted that it is only an approximation.

The official calculation of real wages is more precise. The MHLW uses the formula: Real Wage Index = (Nominal Wage Index ÷ Consumer Price Index) × 100, setting a base year (for example, 2020 = 100) and then publishing the result as an index. Therefore, the figures I calculated may differ somewhat from the government’s official statistics. However, both approaches are useful for understanding the general trend.

This graph provides an overview of the changes in Japan’s nominal wages, consumer prices, and real wages. Overall, wage growth in Japan has remained modest for many years, while consumer prices have risen more sharply, particularly after the global COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, even when wages increased slightly, the faster rise in prices reduced the actual value of workers’ income, making the decline in purchasing power more visible.

Looking specifically at the data for 2023, wages increased by 2.1% while prices rose by 3.2%. This means that although nominal wages went up, real wages turned negative, indicating that living standards actually declined when inflation was taken into account.

Fortunately, in 2024, wage growth outpaced inflation, leading to a slight recovery in real wages. However, Japan is still in an era of low growth and low interest rates, so it remains uncertain whether this improvement represents a lasting trend or just a temporary rebound. Careful observation will continue to be necessary in the coming years.

The Reality of Japanese Companies as Experienced by a Foreigner

I am a Korean who has lived in Osaka and worked for about ten years, during which I experienced four different companies. Please note that my personal experiences cannot represent all Japanese companies, as they are purely individual and subjective. In addition, I have also referred to stories from people around me.

1. Generally low wages

According to a 2025 survey by the Japan Institute for Labor Administration(労働行政研究所), the starting salary for new university graduates at companies listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange Prime Market was about ¥250,000. In Japan, about 20% is deducted for taxes and social insurance, so the take-home pay is around ¥200,000. In major cities such as Tokyo and Osaka, it is difficult to save money on this income if you live alone.

2. Low wage growth

While there are exceptions, in most cases salaries increase only slightly after annual or semi-annual performance reviews. Some people I know have seen their monthly pay rise by ¥100,000, but in many other cases salaries only increased by a few thousand yen, or were even frozen due to poor company performance.

3. Rising consumer prices every year

Especially after COVID-19, prices in Japan have been rising each year. When wage growth fails to keep up with inflation, real wages decline. I keep a household account book every month, and although my standard of living hasn’t changed much, I clearly feel that living costs have become heavier compared to a few years ago.

4. No Legal Guarantee for Bonuses and Retirement Allowances

In Japan, bonuses and retirement allowances are not guaranteed under the Labor Standards Act. Therefore, bonuses are not necessarily paid and often depend on the company’s financial situation. In severe cases, they may not be paid at all, or only a very small amount is given due to poor management. In addition, relatively few companies operate a retirement allowance system, making it difficult to expect additional income beyond the regular salary.

Comments